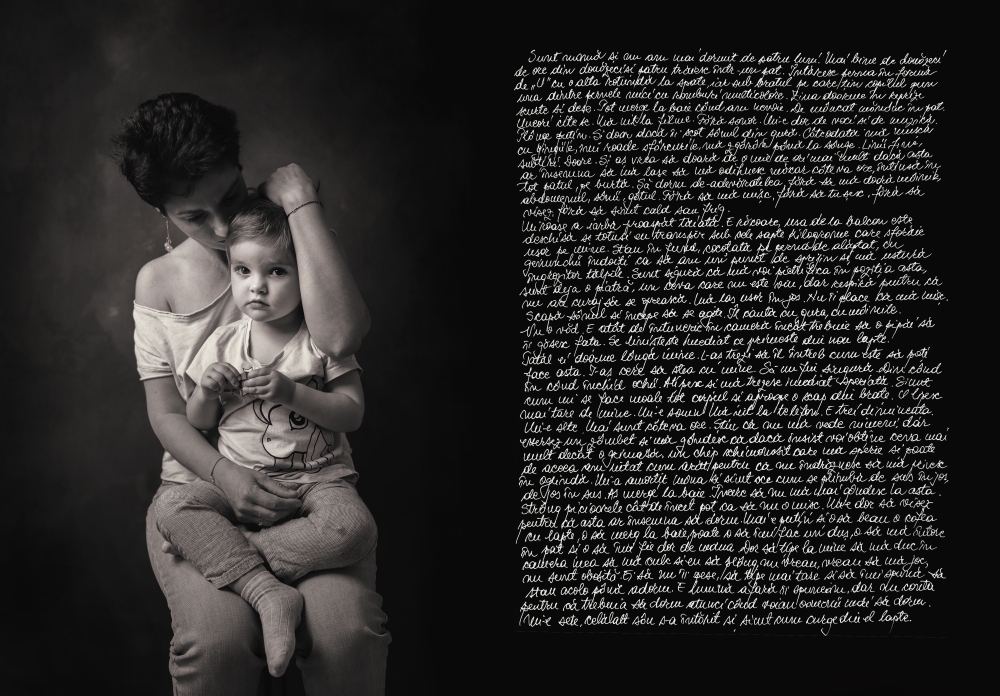

Am crezut că iubirea unei mame poate învinge orice. Așa citisem, așa auzisem. Pe 7 septembrie 2020 l-am născut Lucas. Și acum mi-e greu să exprim exact în cuvinte câte emoții am simțit, la un loc, atunci când l-am vazut. Primele trei zile am fost doar noi doi. Cu o lună înainte, mama pierduse în fața cancerului. De aproape un an ne străduiam să ne ținem firma încă pe piață, într-o vreme în care mai toate proiectele s-au oprit și mai totul era despre pandemie. Am lucrat în ziua în care am născut și multe zilele după, printre picături. Dar nu conta, am crezut că o să fiu puternică, eu, pentru amândoi.

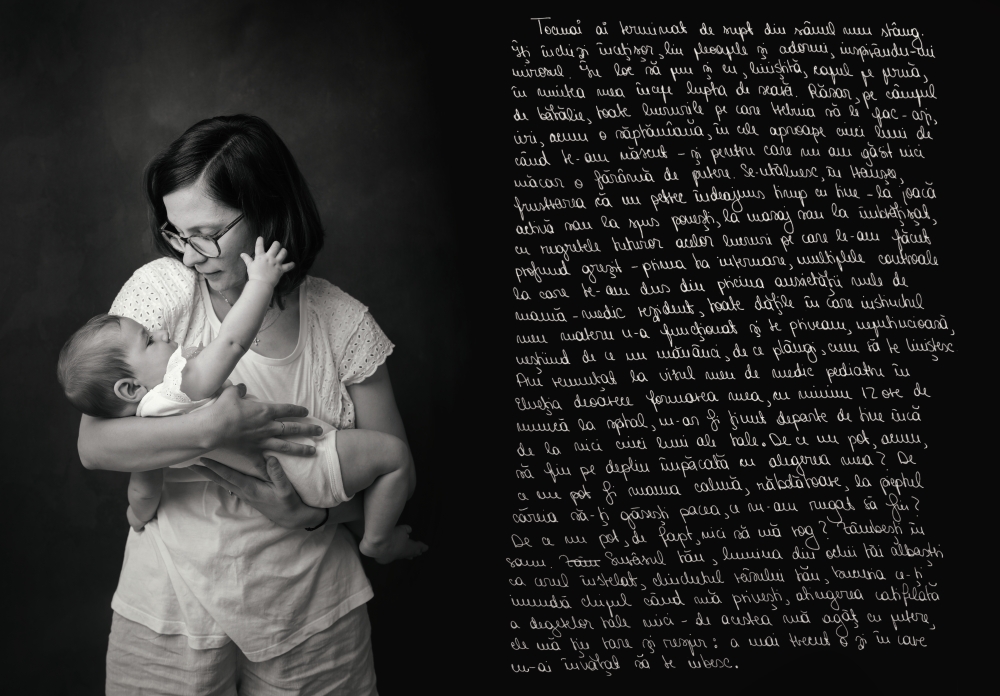

O lună mai târziu, însă, simțeam cum totul începe să se învârtă la o viteză cu care abia mai puteam să stau în picioare. După sute de treziri din oră în oră noaptea, greul alăptării, coșmaruri, insomnii, atacuri de panică, dureri fizice uneori insuportabile, plâns mult și des în adâncul sufletului, eforturi de a fi mama perfectă și ore de muncă pe apucate aproape zi de zi… am început să nu mai fiu așa puternică. Mintea mea s-a sufocat, s-a supărat.

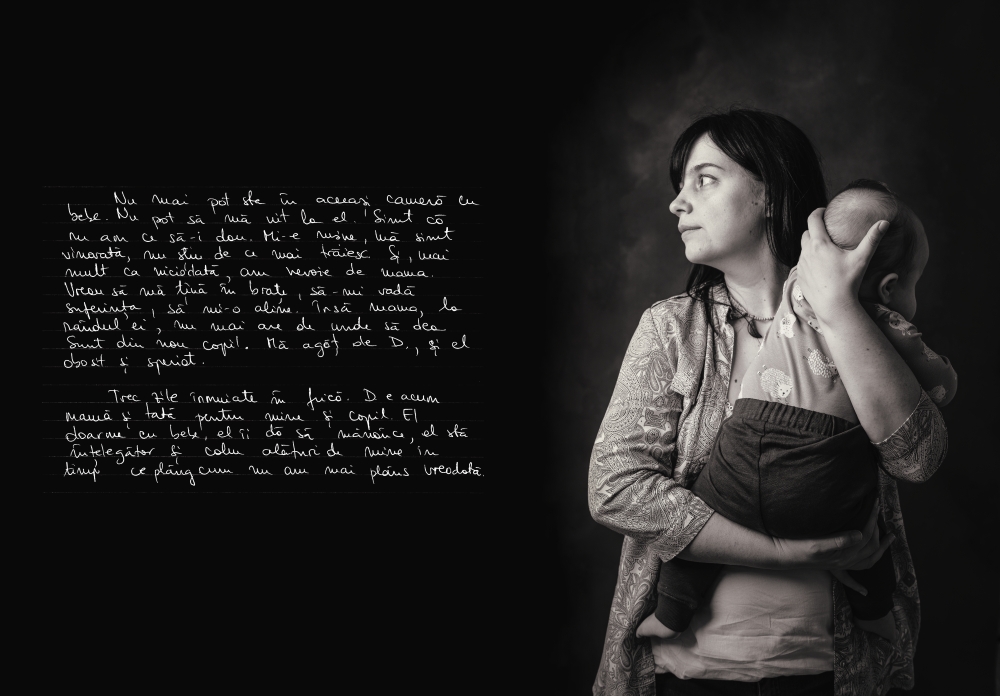

Trei luni mai târziu mă simțeam singură, deși nu eram. Tristă, neputincioasă, urâtă, greșită, din ce în ce mai des. Parcă viața mea mă depășea la kilometri distanță și nici toate cărțile citite nici toată iubirea în jurul meu nu mă puteau ajuta să mă readun. M-am târât vreo 5-6 luni, la propriu și la figurat: între bucurie și deznădejde, între momente frumoase și depresie, între hiperactivitate și letargie, între bebe și doliu, între zile bune și grele. Între zeci de analize, drumuri le doctor și terapie. Între recunoștință că înțeleg ce mi se întâmplă și furia că nu înțeleg de ce.

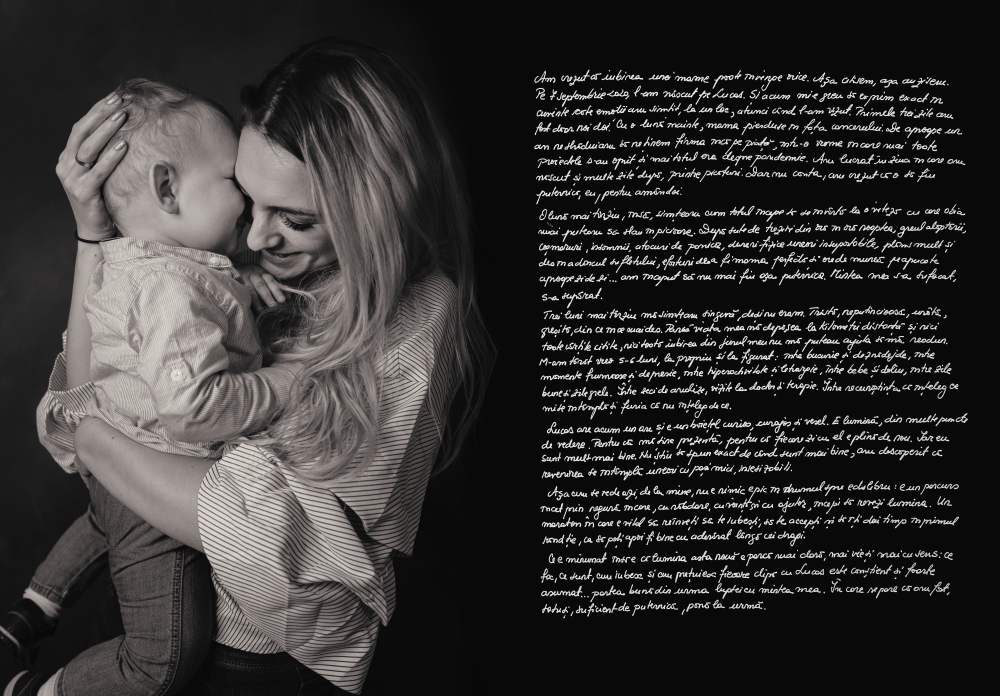

Lucas are acum un an și e un băiețel curios, curajos și vesel. E lumină, din multe puncte de vedere. Pentru că mă ține prezentă, pentru că fiecare zi cu el e plină de nou. Iar eu sunt mult mai bine. Nu știu să spun exact de când sunt mai bine, am descoperit că revenirea se întâmplă uneori cu pași mici, insesizabili.

Așa cum se vede azi, de la mine, nu e nimic epic în drumul spre echilibru: e un parcurs încet prin negură în care cu răbdare, cu voință și cu ajutor, începi să revezi lumina. Un maraton în care e vital să reînveți să te iubești, să te accepți și să îți acorzi timp în primul rând ție, ca să poți fi cu adevărat bine lângă cei dragi. Ce e minunat însă e că lumina asta nouă e parcă mai clară, mai vie și mai cu sens: ce fac, ce sunt, cum iubesc azi și cum prețuiesc fiecare clipă cu Lucas este conștient si foarte asumat, partea bună din urma luptei cu mintea mea. În care pare că, totuși, am fost suficient de puternică, până la urmă.

—

I used to believe that a mother’s love can overcome anything. That’s what I had read, what I had heard. On September 7th 2020 I gave birth to Lucas. Even now it’s difficult for me to express through words how many different emotions I felt, at once, when I saw him. We were alone for the first three days. A month before, my Mom had lost the fight with cancer. For almost one year we had struggled to keep our business alive, in a time when almost all the projects stopped and everything was about the pandemic. I worked the day I gave birth and many days after, by fits and starts. But it didn’t matter, I thought I would be strong enough for both of us.

However, one month later, I felt how everything started to spin at a speed that would make me barely stay on the ground. After hundreds of awakenings each hour at night, the struggle with breastfeeding, nightmares, insomnia, panic attacks, sometimes unbearable physical pain, lots of crying inside my soul, efforts to be the perfect mother and hours of hit or miss work almost every day… I began not to be that strong anymore. My mind choked, it turned mad.

Three months later I felt alone, even though I wasn’t. Sad, powerless, ugly, wrong, more and more often. It seemed as though my life was surpassing me, miles away, and not even all the books I had read or the love around me could help me pick myself up again. I literally crawled for 5-6 months: between joy and hopelessness, between beautiful moments and depression, between hyperactivity and lethargy, between the baby and the mourning, between good days and hard days. Between tenths of analysis, doctor visits and therapy. Between gratitude that I understood what was going on with me and the rage that I didn’t understand why.

Lucas is now one-year-old and he’s a curious, brave and happy little boy. He’s light, from many points of view. Because he keeps me present, because each day with him is full of novelty. And I’m a lot better. I can’t tell exactly since when I’ve felt better, I’ve discovered that the comeback sometimes happens with small, intangible steps.

As one can see today, in my case, there’s nothing epic on the road to equilibrium: it’s a slow journey through the darkness, in which, with patience, will and help, you begin to see the light again. A marathon in which it’s vital to learn to love yourself again, to accept yourself and give yourself time, above all, in order to be truly well near the dear ones. What’s wonderful is that this new light seems to be clearer, more alive and more meaningful: what I do, what I am, how I love today and how I cherish each moment with Lucas is conscious and very assumed, this being the good side of the fight with my own mind. A fight where it seems that I was strong enough, after all. (Ioana Barbu-Cristea)